Movie Review: Godzilla Minus One

Godzilla, debuting in the eponymous film released in 1954 directed by Ishiro Honda and with special effects by Eiji Tsubaraya, is easily one of the most iconic monsters in history. The first film spawned a franchise thirty-three films strong along with international films, comic books, TV, and countless other adaptations. The film laid the groundwork for what would become known as “tokusatsu” media, taking a word that simply means “special filming” and turning it into an entire genre. Emerging in the wake of the post-war occupation, Godzilla served as a vehicle through which Japan could reflect on the horrors of the nuclear bomb, both the destruction and the aftermath of radiation. In the original film, Godzilla is an ancient dinosaur buried beneath the ocean that is awakened by nuclear tests in the sea near Japan. Displaced from its home and charged with radiation, it sets off on a rampage of destruction along the islands of Japan towards Tokyo. The following decades have brought numerous interpretations of the monster with different origins, abilities, and a fast-and-loose relationship with the original metaphor of the nuclear bomb. It has been a rabid monster, a malicious villain, and, at times, an anti-hero protecting the world from even greater threats. In the past decade, there have been four Godzilla films released. Three of them are part of Legendary Pictures’ “Monsterverse”: Godzilla (2014), Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019), and Godzilla vs Kong (2021). These three films will be joined by Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire set for 2024. These films reimagine Godzilla as a violent but noble protector of nature who fights other monsters who would disrupt that delicate balance. The films have varied in terms of scope and scale, with the first film dealing with the military response to the sudden appearance of giant monsters while the most recent film saw the human cast using hover ships to escort King Kong to the center of the Earth. It remains to be seen just how the next film will continue to grow this new franchise.

Until 2023, the only Japanese film to be released was Shin Godzilla (2016). This film was a reimagining of the original film in a modern context as a part of Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi’s “Shin Superhero Universe”. Rather than focusing on the bomb, the film addressed the modern day concerns about nuclear power, referencing the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear plant in 2011 and, at times, satirizing the government’s slow and red tape-laden response. The film was critically acclaimed and won seven Japan Academy Prizes including “Picture of the Year” and “Director of the Year”. The last ten years have seen the King of the Monsters examined and interpreted through a variety of lenses. One oft-levied complaint, however, is the lack of an engaging human cast. The films are often “grounded” in thread-bare stories about people trying to fight, survive, or engage with the monster that serve mainly as vehicles to take the film from monster-scene to monster-scene. It is rare and generally unexpected to see a Godzilla film which is interested in taking its human characters on an arc of growth.

Godzilla Minus One breaks the franchise loose of that cycle with a deeply personal tale set in 1945 just as World War II was ending. Written and directed by Takashi Yamazaki, Godzilla Minus One begins with its protagonist, Koichi Shikishima, landing on an island provisioned with a Japanese military station. The lead mechanic at the station quickly deduces that Koichi is a kamikaze pilot who has fled from duty. Rather than rebuking him, he appears sympathetic and does not report him. That night, the base is attacked by a dinosaur-like monster which quickly demolishes the structure and begins massacring the engineers. At the engineer’s behest, Koichi runs to his plane in order to use its guns on the monster, but he panics before he can fire and is knocked unconscious. He wakes the next morning to find that the monster has left and Tachibana, the lead engineer, is the only survivor. Tachibana blames Koichi for his inability to act, leaving him with mementos from each of the engineers to remind him of his failure. From there, Koichi returns to Tokyo to find that his parents were killed during the bombing raids that left his neighborhood in ruins. Desperate for shelter, he finds himself living with a young woman named Noriko and a baby she’s rescued named Akiko. Koichi begins to find new purpose in supporting them and chooses to take a well-paying but risky job as a minesweeper, joining a small crew to take a boat out and detonate mines to help make the waters safer. He finds satisfaction in his work and gradually begins to regain his will to live, until reports of a monster empowered by recent nuclear tests begin to surface...

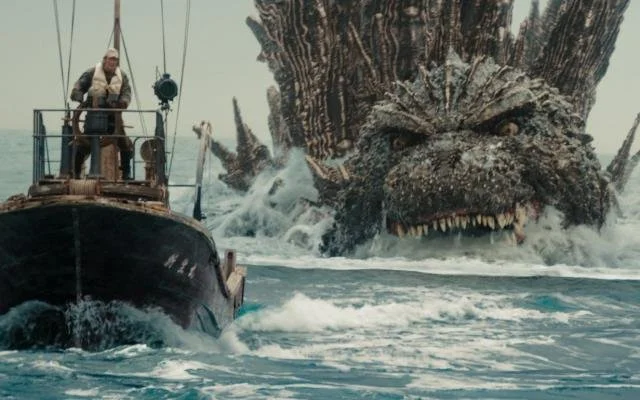

Godzilla Minus One/TOHO (2023)

Contrary to the historic setting, the film highlights just how far digital effects have come in just the last ten years. Whether it is tearing through a military base or surging through the sea after a repurposed fishing boat, Godzilla is tangibly present. The film does not shy away from visceral action when Godzilla tears through the recently rebuilt Ginza district in Tokyo, demolishing buildings and ripping trains to shreds. The rampage also includes a darkly comedic reference to a particularly zealous news team. The viewers are once again treated to another reimagining of the famous “atomic breath” as well. Where Shin Godzilla went with a focused laser beam while Legendary Pictures has been using blue fire, this film depicts Godzilla’s deadliest attack as a single burst of energy creating a massive explosion not unlike a nuclear bomb. Much like a nuclear bomb, the terror of the explosion pales in comparison to what happens in the aftermath leading to an award-worthy performance by Ryunosuke Kamiki.

Rather than focusing on modern nuclear anxieties, the story returns to the roots of the monster in a story set in the direct aftermath of the war. Koichi is a tortured soul, plagued by survivor’s guilt for abandoning his mission to die for his country. He slowly finds meaning in his new family and friends, but is unable to escape the trauma of the war. His mind is reflected in the city around him as it slowly rebuilds itself from the rubble. As his outlook improves, his fortunes turn, and his ramshackle hut is rebuilt into a warm and comfortable home for his family. Sadly, the reconstructed city and Koichi’s newfound happiness are all too vulnerable when Godzilla strikes. Compared to Legendary’s “guardian of nature” and Shin Godzilla’s tortured mutant abomination, this version of the famous monster is downright demonic. It is an engine of destruction and seems driven to cause as much chaos as possible. Despite being smaller than usually depicted, it is all the more terrifying because it can look directly at its victims. Yamazaki has mentioned being inspired by Spielberg films such as Jaws which is fiercely apparent in a scene where our protagonists are desperately fleeing on a boat while Godzilla gives chase despite them throwing everything they’ve got at it. Throughout the entire sequence, they are staring directly into its eyes. They aren’t random passersby getting trampled because they are beneath Godzilla’s notice. At that moment, there is no question that they are the specific targets of its wrath. There’s an intensity and an immediacy to the monster that hasn’t been present for some time. The monster proves capable of shrugging off most damage and the few injuries it does receive are quickly healed without slowing its rampage. The image of Godzilla’s flesh knitting back together while it chases after its prey will likely go down as one of the most haunting images in the franchise.

“We’re gonna need a bigger boat.” Godzilla Minus One/TOHO (2023)

While the film is not shy about spectacle, it never stops being about the human cast. Each member of the cast is turning in a stellar performance and they remain the most compelling part of the film even in the midst of Godzilla rampaging through Tokyo. Rynosuke Kamiki deserves special mention for his performance as Koichi Shikishima. Post-traumatic stress disorder was not added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until 1980 and even then was considered controversial. Koichi is struggling with something that, in 1945, very few people understood and even fewer would have been able to help him with. Yet, through Kamiki’s performance, Koichi conveys his struggle without the need for formal terminology. When he wakes up in a panic and needs to be assured that the war has ended and that he’s not simply dreaming of being happy, it is truly heartbreaking. He’s as much a victim of the war as anyone around him, yet he is the one being blamed for surviving. It helps that he is surrounded by a group of friends and a partner who do not fully understand what he is experiencing but love him and try their best to help him through. The bulk of the film does not even feature Godzilla. It is focused primarily on Koichi slowly coming into his own and rebuilding his life. Seeing his happiness heightens the dread for when Godzilla will inevitably rear its head and strike at whatever joy Koichi has managed to find.

Unlike the recent films which have generally focused on the government and other large organizations’ responses to Godzilla, this film takes place at a time when public anxiety is peaking while the government has proven incapable, and at times unwilling to address those fears. It is a feeling relatable to anyone who lived through the recent pandemic. The film does not shy away from criticizing the Japanese government’s short-sighted planning and lack of consideration for the value of life during the war. The fact that Japanese planes did not have ejector seats is brought up multiple times to underline that point. Even beyond the war, it is made apparent that citizens were left to fend for themselves in the reconstruction, leaving many to starve or freeze to death. It takes the cooperation of a community of survivors to rebuild their homes and take back their lives. By focusing on the human cast, the film creates a gripping climax when the motley crew of volunteers venture out in a last-ditch effort to stop Godzilla. The film clearly understands that the stakes for this film are not as large as a country or even as a city. It is about a small group of people struggling to survive tragedy after tragedy and refusing to give up on rebuilding their lives.

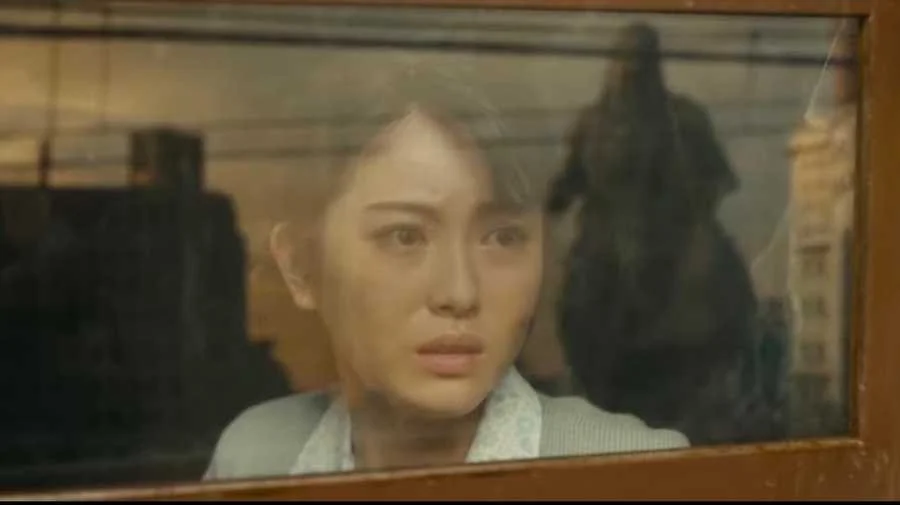

Koichi (Ryunosuke Kamiki) and Noriko (Minami Hamabe). Godzilla Minus One/TOHO (2023)

Compared to most kaiju films which revel in the mass destruction and take no issue with massacring large crowds of faceless individuals, Godzilla Minus One takes a uniquely intimate approach with its stakes and is all the stronger for it. Focusing on one of the lowest points in Japan’s history and sending Godzilla to drag it even further down could easily lead to a film too bleak to watch. Instead, by focusing on a core group of characters rebuilding from ashes, the film reminds us that no one is an island and, at the end of the day, relying on each other is how tragedies are overcome. By balancing a heartfelt story with some truly spectacular visuals, Godzilla Minus One may just go down in history as the definitive depiction of the famous kaiju for our age.